Where Continuous Deployment ends

You have heard about Continuous Delivery or Continuous Deployment, don’t you? Apart from abstract definitions we showed you how one can perform deployments with the help of Gradle, Ansible, and Docker. A quite complete example project has been published at GitHub.

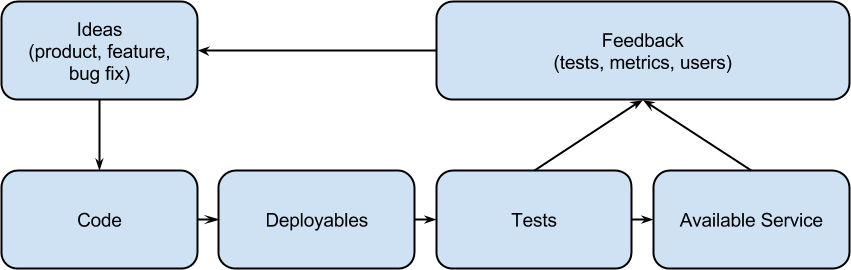

Most deployment pipelines contain the steps in the figure below. The order of creating deployables and performing tests doesn’t really matter, both steps might even be performed asynchronously.

But do deployments end with the newly released application being available on the production server? Unfortunately not: using an automated deployment pipeline comes with other consequences.

Deployment Doesn’t End on Prod #

You’ll need to ensure that there aren’t any breaking changes on different layers. For example the database should support both new and old applications as client. The application itself should be capable of serving older clients like another service or an older browser instance of the frontend. Even the frontend code in the browser needs to be updated at any point in time. How would you ensure the user doesn’t perceive updates in a bad way?

Then, how do you as developer or service provider know about the health of your application? How do you know about the users accepting or ignoring your shiny new features? Who wakes you at night, when your application doesn’t behave like it should?

There’s more to DevOps #

Even without a very clear definition of DevOps - maybe there’s a broad agreement on its properties - you might have experienced that it helps breaking some barriers between the Ops and Dev silos. With a team of developers and most of them having an affinity to operational tasks you certainly don’t need operators to deploy your application anymore. Operations can shift their tasks to become an infrastructure provider, probably even deciding to delegate most of their tasks to AWS or DigitalOcean.

But the developers now need to understand their own aplications, databases, network, storage, or even hypervisor to a higher degree. They need to learn how database maintenance looks like. Developers need to understand which implications it has to increase the deployment frequency, which part of a system fails first in cases of higher load, and how the users’ behaviour has an impact on application availability.

Developers can learn from operations (while also teaching them e.g. about infrastructure as code) and they should. Why? Because it’s their application and they know it best. There’s little value in waking up one of the operators only to have them call a developer at night.

So What? #

The point is: Developers need to take responsibility for their whole application, including its database and big parts of its infrastructure. They continuously deploy an application, so they need to handle every aspect of the pipeline and a production environment. Tools like Ansible and Docker make it easy for them, but tools are only valuable when the user understands them.

With such a responsibility in mind, developers can design an architecture which is flexible and resilient to temporary issues or environmental aspects. An architecture being designed by developers has a higher chance to be accepted by themselves. Apart from working to only get money, people want to be motivated. Motivation comes with fun and I guess a happy developer is a better developer.

Back to the deployment pipelines. And where they end. They don’t end on production - sorry.

What Comes After Prod? #

A responsible developer wants to sleep well. They don’t sleep well after the successful deployment on prod. They only sleep well when they can be sure that if something bad happens, they’ll be notified.

How do they know if everything is ok? They introduce monitoring. They add feature toggles. They design their services backwards compatible and they make their endpoints resilient to timing issues or errors of other services. They don’t only automate a deployment, but they automate every other aspect, too.

Monitoring and Alerting #

Monitoring helps collecting metrics about service behaviour and health. Simple service availability checks with tools like Pingdom are a good start. Monitoring over a time range allows to infer what’s normal and what’s an incident: you don’t need too much artificial intelligence when finding out in which range an average memory consumption lies.

Alerting based on the collected metrics becomes simple: observe behaviour over one or two weeks, define rules which allow some fuzziness, and trigger alerts when your rules are violated. Alerts can be managed by services like PagerDuty, or simply sent via email, tools like HipChat, or even Twitter.

You certainly don’t need to build yet another monitoring or alerting system - there are lots of them out there. Well known tools like Nagios and Icinga are still valid and stable, but if you’re looking for fresh concepts, you might want to try Prometheus. It comes with everything you’ll need: so-called exporters to expose host or application metrics, a server to collect and store them, and an alertmanager to handle rule violations. With an upcoming release of the alertmanager you might even try to automatically recover issues by triggering generic webhooks.

Though especially the alertmanager isn’t declared as stable enough to use it right now as an infrastructure’s backbone, there’s high potential with the overall concept behind it.

Feature Toggles? User Feedback! #

Apart from maintaining a running system and observing its healthyness, there’s some value in developing new features. Ah, well, features are the reason why your users want to use your service!

But how do you handle bigger features, which need to be implemented over several days and which aren’t finished by only one single deployment? Do you stop your deployment pipeline until the feature is complete? How would you quickly deploy bug fixes then? When using feature branches, how do you continuously perform tests and canary deployments? When do you consider a feature to be complete?

One way of handling half baked features is to deploy them to production, but not enabling them. Feature toggles are a way of disabling them. You can even partially enable them to only a small part of your users - do you have beta testers?

When continuous deployment is about fast feedback cycles, don’t forget the user! They give you valuable feedback. You decide how they contact you: as a surprised user who is angry about a bug or as someone who knows that you’re able to quickly fix bugs (maybe still angry, though).

Tell the user about continuous delivery and build a community. Just like operations and developers tear down barriers, you can embrace your users and integrate them as early as possible into your development cycle.

Feature toggles help you to hide unfinished code, but adding an easy way to submit feedback integrates your users.

Summary #

Changing a culture to apply DevOps methods has consequences. Developers don’t only write software anymore, but are on call. They probably have user contact. Whoo! That doesn’t mean life to become harder, but it’s the chance to embrace change. Change is good!

Developers need to perform operative tasks like monitoring and they need to handle user feedback. Continuous delivery forces people, teams, and enterprises to think about new ways to handle incidents, implementing new features, and talking to the user.

Feedback cycles don’t end with the tests or health checks. A complete pipeline integrates user feedback. So the figure above needs to be fixed and can look like this:

There is no end of your deployment pipeline. Only when you close your service or when there isn’t any user. 😉